Herstory 101: The Unknown Mothers of the Americans with Disabilities Act

On July 26, 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law, providing monumental–and overdue–protections for people with disabilities. The most famous names associated with the passage of the ADA are President George H.W. Bush, Senator Lowell Weicker and Representative Tony Coelho, who have been referred to as the drafters of the bill, and Justin Dart Jr.–also known as the “Father” of the ADA. However, there are several names that are often left out of historical accounts, despite being instrumental to the ADA’s passage. Women dedicated their blood, sweat, and tears (as they have through almost every historical moment) to achieve equality in society, and we’re shining a light on a few who have been left without recognition for the role they played in bringing forward this historic law.

Judith Heumann

“It is no longer acceptable to not have women at the table. It is no longer acceptable to not have people of color at the table. But no one thinks to see if the table is accessible.”

Judith Heumann contracted polio at only 18 months old, which left her permanently needing a wheelchair to travel. As a young child, she was prohibited from attending her local public school as they deemed her a “fire hazard” due to her inability to walk. While in college at Long Island University, Heumann joined multiple advocacy groups for disabled people before starting her own called Disabled in Action (DIA), in which she would fight for many disability accommodations such as ramped buildings. After college, she applied for a teaching license and was denied, again, for being a “fire hazard.” This time, Heumann sued the New York City Board of Education and won–making her the first wheelchair user to teach in New York City.

As part of her advocacy, she was able to pressure President Richard Nixon into signing the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was the first federal civil rights legislation for people with disabilities. However, when the protections of the act were not sufficiently enforced, she led the 504 Sit-in, with over 100 disabled activists, named after the act’s section on disabilities. The sit-in lasted 28 days and demonstrated the strength of disabled people in America. The protest was hugely successful in accomplishing its goals and provided the foundation for the ADA.

Heumann was acknowledged for her work in Time magazine in their “100 Women of the Year” piece as the woman of 1977 after gaining fame in the documentary “Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution.”

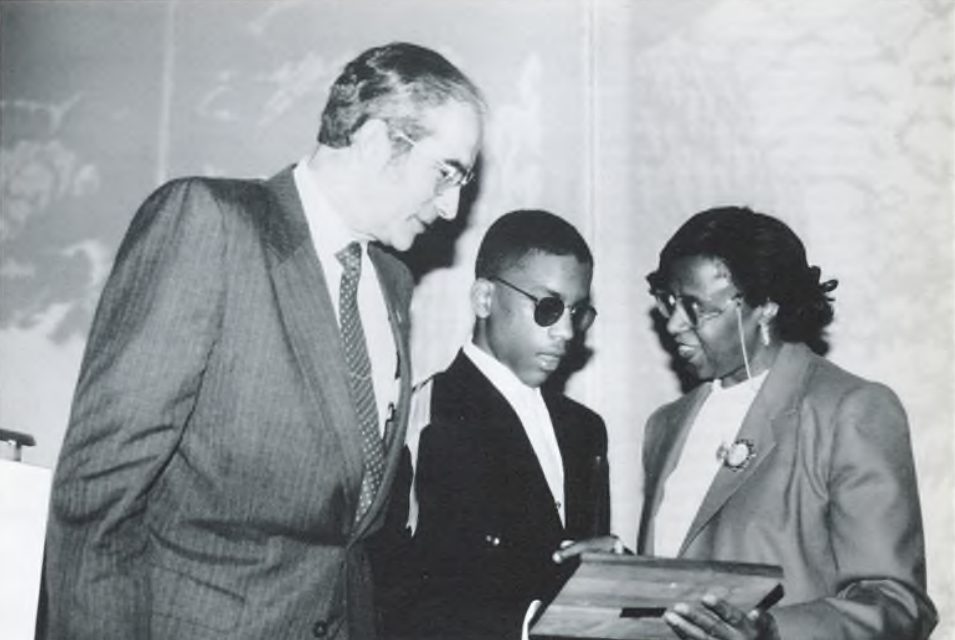

Sylvia Walker

Sylvia Walker was born with impaired vision and was diagnosed as legally blind by the age of 14. She faced forms of ableism during her schooling years and fought to combat discrimination against disabled people in her adult life. After attending college, she accepted positions at Hunter College and Howard University.

During her time there, the Howard University Research and Training Center was opened. She conducted research predominantly on disabled minorities and what resources were needed for rehabilitation. This work was extremely important as members of the disabled community were disproportionately low-income people of color, and their studies showed that low-income, non-white populations faced higher rates of inadequate healthcare, nutrition, and housing and substance abuse compared to their white counterparts. Walker further studied the intersection of poverty, race, and disability at the Research and Training Center.

Walker’s and her team’s work and research at the Howard University Research and Training Center supported the development of the ADA which was heavily impactful in its passing.

Patricia Wright

“So each one of those things that nondisabled kids take for granted become the linchpin of people with disabilities lives.”

Patricia Wright, who is legally blind, began her activism career as a personal assistant to Judith Heumann at the 504 Sit-in. She went on to co-found the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) in 1979 with Mary Lou Breslin and Robert Funk. She continued to be a strong advocate for disability rights and fought to enact the Handicapped Children’s Protection Act of 1986. This bill changes the Education section of the Handicapped Act to grant reasonable attorney’s fees, expenses to the parent or guardian of a handicapped child who wins a civil suit under the Act to protect their right to a “free appropriate public education.” She also succeeded in introducing amendments to the Fair Housing Act regarding people with disabilities.

Additionally, when the Reagan administration threatened to get rid of or minimize regulations administering Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, Wright led a grassroots lobbying campaign that resulted in over 40,000 cards and letters of support for her cause. This initiative was incredibly successful as the threats were ultimately dropped.

Wright pushed and lobbied for the ADA and is nicknamed “the General” for her leadership and campaign style. She received the George Bush Medal in 2000 for her work and the Presidential Citizens Medal in 2001.

What can we learn from these women?

While this was by no means a comprehensive list of the women who impacted the creation and passage of the ADA, these women along with the others all have a few things in common:

- Firstly, they all cared about the people and issues around them and wanted to effect change and a more equal society.

- Secondly, none of them were in office, but still very much had the capability to make a difference. These women did not grow up in political families nor did they become lawyers then politicians. They were everyday women, yet extraordinary, who faced challenges and overcame them to fight for a more inclusive world. Imagine what they would have been able to accomplish if they were in office and could have enacted legislation themselves.

There is this misconception that there is a specific path one must take to successfully run for office. These women serve as an inspiring reminder that the “qualifications” for making a difference are simply this: if you care, you’re qualified to create change.

Join the She Should Run community to connect with other women and share your journey!

Citations:

https://www.congress.gov/bill/99th-congress/house-bill/1523

https://mn.gov/mnddc/ada-legacy/ada-legacy-moment26.html

Image 1: TedTalk

Image 2: unknown

Image 3: unknown

Enjoying our blog content? Help pay it forward so more women are able to wake up to their political potential. Donate to support She Should Run.